I’m thrilled to welcome my dear friend and critique partner, Cynthia Roemer back to Romancing History. In the past, Cynthia has shared some of the history behind her novels. Today, I’m sharing an interview with this talented writer so my readers can get to know her and her books better.

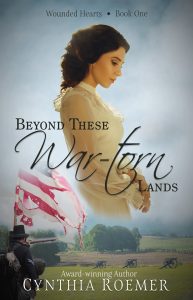

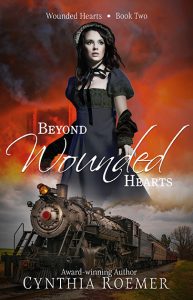

Don’t forget to visit the giveaway section before you leave. Cynthia is generously offering a print copy of her latest release, Beyond Wounded Hearts, to one lucky Romancing History reader.

Fast Five

- Sound of Music or Hello Dolly? Definitely Sound of Music. One of my favorites!

- Kindle, Audiobook, or Paperback? I love a book in my hands.

- Dark or Milk chocolate? Milk chocolate!! Is there any other option? LOL!

- Sweet or Salty? Both are good. Sweet probably wins out. =0

- Sports or Boardgames? In my younger years, I loved playing volleyball. But board games or party games are more my speed nowadays.

Author Q & A

RH: Tell us a little bit about yourself. How long you’ve been writing? How many books you have published and what era(s) do you write in? If you’re comfortable sharing some personal details about yourself that would be great! Readers love to know about an author’s daily life.

CR: I’m a farmer’s wife, mom to two grown sons (the oldest of which is married). I love living in the country, enjoying God’s creation. When not writing, I enjoy hiking, biking, gardening, baking, discovering new birds, and riding side-saddle with my hubby in the combine during harvest.

I dreamed of becoming a published novelist since my junior year in high school when a story I wrote earned first-place in a local college competition. I wrote my first draft of Under This Same Sky (my debut novel) while in college, but soon discovered the journey to publication wouldn’t be an easy one. A few rejections and meeting my future husband put a damper on my novel ambitions. But as I married and raised our two boys, I continued to write and had numerous short-stories and articles published.

When my boys were teens, the novel bug bit me again. I got plugged into American Christian Fiction Writers and realized I had a lot to learn. Fast-forward a couple of years of learning the craft, numerous re-writes, gaining insights from lessons and critique partners, and entering contests, and I met an interested publisher at a writer’s conference. A month later (twenty-some years after I’d written my original book draft), I signed a three-book contract for my Prairie Sky Series.

The series is set on the Illinois prairie in the mid-1800’s). I now have two books in another Civil War era series in print (Wounded Heart Series) and am beginning work on Book Three. I also have a Christmas novella coming out this October (which Kelly knows a little something about since she’s one of the authors as well!) All my novels have a strong spiritual thread woven into their historical storyline.

RH: I’m so proud of you for keeping the dream of being a published novelist alive and that you always honor God with your talents. Now tell us something unusual about yourself. Something not in the typical back of the book author bio—something quirky.

CR: The quirkiest thing I can think of is I can talk like Donald Duck. =). Now, it’s important to note, I was voted Most Shy in my high school class. My bravest moment came one day in English class when I sang When the Saints Go Marching In (Donald Duck style) from behind my textbook while my classmates swayed back and forth and sang backup. My English teacher was never so stunned than to learn it was me behind that voice. LOL

RH: I can’t even picture you doing this. You do realize I’m going to request a solo during our next Zoom visit, don’t you? LOL! Let’s move on. Which historical figure, other than Jesus (because who wouldn’t want to meet Jesus?), would you like to meet? Why?

CR: Such a tough question. I’m not sure I can narrow it down to just one, but I would love to meet David from the Bible. He was such a godly young man with such strong faith. In more recent history, I would love to meet Lou Gehrig or Thomas Edison. Both had such stamina and drive to keep trying. I respect that

RH: Yes, I love Edison’s tenacity. That is a very admirable trait. Which 3 words describe the type of fiction you write?

CR: Inspirational, relatable, unpredictable

RH: I’d definitely agree with your choices. I would also add that your novels are thoroughly researched and filled with the kinds of historical tidbits that readers of the genre love to discover. What unpublished story do you have in your stash that you really hope sees the light of day someday?

CR: A couple years ago, I entered a Hook Contest and was chosen as a finalist. For those who may not know, a hook is a one-sentence description of a book with the intent of luring readers in and making them want to read it. I entered the contest on a whim, never expecting to have my hook chosen. When it was, I had two weeks to pull together a synopsis, blurb, and three chapters. I had nothing!

So, with a lot of prayer and hard work, I completed the required submission material. Though I didn’t win the contest, I fell in love with the story, which I tentatively entitled, Not What They Seem. It’s a bit more light-hearted storyline than I usually write, about a woman on a stage coach who witnesses a robbery and later recognizes the thief as the new town deputy. It’s next on my list of books to write after Book Three in my Wounded Heart Series. I’m looking forward to delving back into it.

RH: Yay! I thoroughly enjoyed reading those first three chapters. I’m glad you’re you have plans to finish it. Do you have a favorite quote from your recent release you’d like to share?

CR: Here are a few of my favorites.

“The thousand flickering campfires dotting the landscape didn’t hold a candle to the splendor of God’s creation.”

“He was either the most genuine man she’d ever met, or the most naïve.”

“This was gearing up to be a battle of the wills. Luke could only pray it would end peacefully and not be the onset of another war.”

“Luke knew enough not to kindle a flame that was certain to scorch him.”

RH: Excellent choices. I think that last one might be my favorite. I totally love Luke and his simmering attraction to Adelaide. If you were to pick a particular Scripture verse as the theme of your novel, what would it be? Why?

CR: I always include a theme verse in my stories that sums up the story. For Beyond Wounded Hearts, the theme verse is Proverbs 16:8:

“When a man’s ways are pleasing to the Lord, he makes even his enemies live at peace with him.”

This verse so embodies my hero, Luke Gallagher. He’s my David from the Bible—a man after God’s own heart. Throughout the story, we see the Lord using his strong faith and persistent godliness to change the hearts of those who call him “enemy.” But Luke, too, has a lesson to learn as he battles guilt feelings from his past.

RH: That verse is so perfect for Luke’s journey in Beyond Wounded Hearts. What scene in your recent release was the hardest to write? Which is your favorite?

CR: Hmm. Possibly the hardest was the opening scene in which Adelaide goes looking for her aunt during the Richmond takeover and tries to save her from a burning building. A lot of research went into describing details of the burning of Richmond and also the intricacies of the fire and injuries sustained.

It’s nearly impossible to choose a favorite scene. Of course I enjoyed the scenes where Luke and Adelaide interact with each other and the final scene (which I choose not to go into detail about for obvious reasons =0). But a couple of other scenes I really enjoyed writing involved Adelaide learning to milk a cow and her awkward encounter with a Union spy. I also enjoyed her conversion scene, and Luke’s unexpected visit from a renegade Confederate soldier. Lots of fun stuff!

RH: Oh, I’d nearly forgotten about Adelaide milking the cow! Winner, winner, chicken dinner! Which secondary character do you think will resonate with readers? Why?

CR: I love secondary characters. They add so much to the story. One character I think readers will identify with and enjoy is Lydia Gallagher, Luke’s younger sister. She is the little sister everyone would love to have—sweet, innocent, forgiving, and loyal. She’s also a teenager in every sense of the word—talkative, adventurous, and a bit unpredictable. Several on my launch team really connected with her. And if all goes well, readers will see more of Lydia in Book Three of my Wounded Heart Series slated to release in spring of 2024.

What do you hope readers will take away after reading your story?

CR: There are numerous lessons to be applied from Luke and Adelaide’s story—grace, forgiveness, self-worth. But most importantly, I want readers to catch a glimpse of how the Lord can use us to speak into the lives of others regardless of our flaws and imperfections. God can use us to touch people’s hearts for Him, if we are willing to step out and let ourselves be available.

RH: That is such an important lesson. God truly delights in using ordinary people to accomplish his great works! What a pleasure having you on the blog today, Cynthia!

CR: Thanks for hosting me! It was wonderful to chat with your readers.

About the Author

About the Author

Cynthia Roemer is an inspirational, award-winning author with a heart for scattering seeds of hope into the hearts of readers. Cynthia enjoys spinning tales set in the backdrop of the mid-1800’s prairie and Civil War era. It’s her prayer that her stories will both entertain and encourage readers in their faith. She resides with her husband on their family farm in central Illinois. Visit Cynthia’s website to signup for her author newsletter or connect with her on Facebook, Goodreads, Author Amazon Page, BookBub, Twitter, and Instagram.

About Beyond Wounded Hearts

About Beyond Wounded Hearts

They were North and South ~ Faithful and Faithless

After suffering disabling burns during the fall of Richmond, Adelaide Hanover awakens in a hospital alone and destitute, escalating her already stanch hatred for Yankees. When the Union soldier who freed her from the rubble begins paying her visits, she wants nothing to do with him … or his faith. Yet, his persistent kindness penetrates her resolve and forges a much-needed friendship. But after a dangerous man threatens Addie, she flees Richmond, intent on solving the mystery to her aunt’s dying wish before he does.

Haunted by a tragic failure in his past, Corporal Luke Gallagher takes Adelaide’s plight on as his own. Though his strong beliefs collide with his growing feelings for her, he offers his family’s home as a place to convalesce. Adelaide’s initial rejection, followed by her sudden willingness to accept his benevolence, hints there’s more to the decision than a mere change of heart. When trouble follows her, endangering her safety, as well as his family’s, Luke must lay his life and his convictions on the line to save them.

Amazon

Giveaway*

This Giveaway is now closed!

Congratulations to our winner,

Renee W!

In her interviw, Cynthia shared a moment where she stepped beyond her comfort zone and sang When the Saints Go Marching In (Donald Duck Style)! LOL! To enter the drawing for a print copy of Beyond Wounded Hearts, share a time you stepped outside of your comfort zone.

*Winner must have a U.S. mailing address. Giveaway ends midnight, Wednesday, April 26, 2023.