Long before Elvis gyrated his pelvis or Miley Cyrus twerked at the VMA’s, the Viennese waltz shocked European aristocracy. Although today the waltz is considered the “Queen of all the dances,” it has a scandalous history.

The Waltz had humble beginnings in rural Germany. In the mid 18th century, peasants began to dance something called the landler in Bohemia, Austria, and Bavaria. Set to 3/4 time music, the dance involved couples rotating around the dance floor. It eventually became known as the walzer, from the Latin volvere, meaning rotate. At the time, the aristocracy was dancing to the minuet but the peasants’ dance was so fun that some noblemen were known to sneak away to the lower class gatherings just to enjoy it.

Eventually the waltz was introduced to Vienna, in an opera called “The Cosarara.” In 1790, Baron Newman introduced the twirling dance to English aristocracy but it was Napolean’s triumphant army that brought the dance to France. Upon its arrival, the Viennese waltz shocked the church and proper society with the prolonged bodily contact not just of the hands, but of the faces and bodies of the dancers. The Anglican archbishops denounced the new fad as a “lust-inducing, decidedly degenerate action.”

While the waltz seems innocent enough by today’s standards, at the time it horrified many of the upper class. Novelist Sophie von La Roche described it as the “shameless, indecent whirling-dance of the Germans” that “…broke all the bounds of good breeding,” in her novel Geshichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim, written in 1771.

The dance was considered so provocative when it was introduced that even the morally challenged Lord Byron felt driven to write:

Endearing Waltz! — to thy more melting tune

Bow Irish jig and ancient rigadoon.

Scotch reels, avaunt! and country-dance, forego

Your future claims to each fantastic toe!

Waltz — Waltz alone — both legs and arms demands,

Liberal of feet, and lavish of her hands;

Hands which may freely range in public sight

Where ne’er before — but — pray “put out the light.”

Methinks the glare of yonder chandelier

Shines much too far — or I am much too near;

And true, though strange — Waltz whispers this remark,

“My slippery steps are safest in the dark!”

What made the waltz so scandalous?

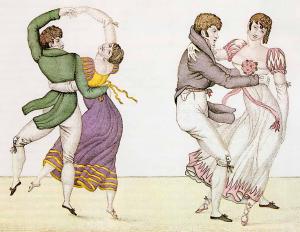

The waltz gained its scandalous reputation because of the “closed” face-to-face position of the dancers. In its day, the waltz was a strikingly intimate and sensuous dance, which was a major departure from the open group dances and stately minuets of previous generations which were characterized by a refined and stylized elegance, polite distance between the dancers, and precise movements. They were much less energetic, characterized by sternness of attitude and slow complex patterns of movement. Most importantly, earlier dances were performed at arm’s length where only the couple’s hands touched. Dancers wore gloves so there would be no fleshly contact even at this distance.

Darcy and Elizabeth dancing the formal dances of the Regency era at the Netherfield Ball, Pride and Prejudice (BBC)

In previous dance forms, the gentleman’s focus was always in steering his partner through the series of intricate steps and maneuvers to avoid colliding with others on the dance floor. Since the only floorcraft required was to keep the partners from overtaking the couple in front of them as they flowed gracefully around the ballroom, the man would not be distracted from giving his lovely partner his full attention.

The intimate postures and intense gazes that resulted were most likely to blame for the waltz’s initial disgraceful reputation. In traditional country dances, there was plenty of eye and body contact, but it was fleeting and partners moved quickly from one person to another. In the Waltz, the eye contact is continuous and unflinching and so is the body contact — with hands, as Byron describes, “which may freely range in public sight.”

Imagine the shock in the courts of Europe when the gentleman’s foot disappeared from time to time under the lady’s gown in the midst of the dance as reported on the Prince Regent’s grand ball from the society pages of The Times of London, summer, 1816:

“We remarked with pain that the indecent foreign dance called the Waltz was introduced (we believe for the first time) at the English court on Friday last … it is quite sufficient to cast one’s eyes on the voluptuous intertwining of the limbs and close compressor on the bodies in their dance, to see that it is indeed far removed from the modest reserve which has hitherto been considered distinctive of English females. So long as this obscene display was confined to prostitutes and adulteresses, we did not think it deserving of notice; but now that it is attempted to be forced on the respectable classes of society by the civil examples of their superiors, we feel it a duty to warn every parent against exposing his daughter to so fatal a contagion.”

According to Jeff Allen, author The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Ballroom Dancing, “The ‘voluptuous intertwining of the limbs,’ simply referred to the close dance position of the day. The gloved hand of the gentleman was placed gently on the waist of his partner at virtually full arm’s length. The lady’s left-gloved hand quite possibly was delicately placed on her gentleman’s shoulder, and she likely held a fan in that same hand. The left hand of the gentleman remained open and acted as the shelf for his partner’s right-gloved hand. The really scandalous point of that reporter’s observation was that the gentleman’s foot disappeared from time to time under the lady’s gown in the midst of the dance. The bodies of the dancers were never in contact!”

The fast pace and consistent twirling of the dance was also a departure from the stately minuets of the past and could prove to be an exhausting and dizzying experience. Cellarius, a French dancing master of the Regency era, warned that, “In close embrace the dancers turned continually while they revolved around the room. There were no steps forward or back, no relief, it was all a continuous whirl of pleasure for those who could take it. The Valser should … take care never to relinquish his lady until he feels that she has entirely recovered herself.”

Needless to say, the more forbidden the dance became the more anxious society was to engage in it. Some of the first members of European aristocracy to be seen publicly favoring the dance were the Emperor Alexander of Russia and Lord Palmerston of England. When they were seen whirling around English ballrooms with grace and skill, the rest of English society quickly joined in.

Most likely it was this “lighter than air feeling” that brought the waltz into acceptance among Europe’s upper class. Johann Goethe, a German writer and statesman, is known to have enjoyed the waltz. “Never have I moved so lightly. I was no longer a human being. To hold the most adorable creature in one’s arms and fly around with her like the wind, so that everything around us fades away…” By 1820, the dance had finally reached respectability as a permanent fixture at balls throughout English society for the majority of the 19th century and early twentieth century thus earning her position as “Queen” of the ballroom.

Do you know how to waltz?