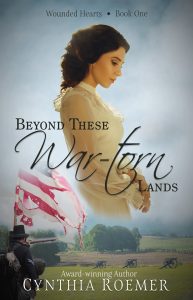

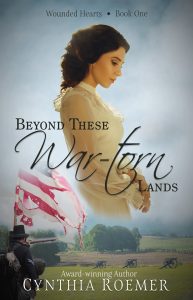

I’m so excited to welcome friend, fellow author, and critique partner, Cynthia Roemer back to Romancing History today. Cynthia’s latest novel, Beyond These War-Torn Lands, releases next Tuesday, August 3rd and I know y’all are gonna love Drew and Caroline’s story as much as I did!

As you can imagine, writing historical romance requires an author to delve into the time period—the clothes, speech patterns, foods, tools, and events of the era in which they write. Today Cynthia is going to share some of the behind-the-scenes research she did to bring her Civil War novel to life on the page.

And, Cynthia is giving away a signed, print copy of Beyond These War-Torn Lands, too! So make sure to see the Giveaway section at the bottom of this post and leave a comment!

When I decided to write a Civil War novel, I knew I was in for a lot of research. I’m not sure how I settled on The Battle of Monocacy Junction to start the novel off (timing, placement), but I soon found myself engrossed in learning about this lesser-known battle along the Monocacy River in Maryland. This battle, though a loss for the Union, turned out to be an ultimate victory for the men in blue.

Here’s why:

The Monocacy River, Maryland

The day-long battle began early in the morning of July 9, 1864 and lasted well into the evening. General Lew Wallace commanded the Union troops, while General Jubal Early led the Confederates. The two sides volleyed back and forth throughout the scorching heat until they landed smackdab in the cornfields and yards of some of the neighboring residents—the Best family, Thomas family, and Worthington family.

Several of the residents, such as six-year-old Glenn Worthington and his older brother Henry, hunkered in their cellars watching the battle through cracks in the walls. Glenn later wrote an account of the experience in his book, Fighting for Time.

Waves of skirmishes ended with Wallace’s men fleeing, leaving a horde of dead and wounded in their wake. The Confederate army had intended to storm Washington and take over the city. However, the delay at Monocacy Junction allowed the Union time to send for reinforcements and spare their Capital a takeover. Therefore, the battle at Monocacy became known as The Battle That Saved Washington.

As I was delving into my research, our hostess, Kelly Goshorn, and I had just become friends and critique partners. When I found out she lived within an hour of the very battle I was researching, and that the site had been preserved for visitors, I was ecstatic! Though Kelly hadn’t visited the site herself, she graciously offered to house me if I was able to make the trip out. I had high hopes of doing so and then … the Pandemic hit.

Followed by a cancer diagnosis.

Between the two unexpected challenges, I knew I would be unable to make the trip. But thank the Lord for carrying me through my health ordeal and for all the wonderful online resources available. Via the internet, I was able to access so much information about the National Battlefield at Monocacy Junction, among other historical events and people that found their way into my novel, Beyond These War-Torn Lands. Kelly proved a help as well, for she had visited some of the sites included in the book.

In the opening scene of Beyond These War-Torn Lands, my hero, Sergeant Andrew (Drew) Gallagher, is injured at the Battle of Monocacy Junction and would have become a casualty of war had my heroine, Caroline Dunbar not happened upon him while on her way to aid wounded Confederates at her neighbors—the Worthington and Thomas families.

How I relished weaving my characters into history during one of America’s most challenging and fascinating eras. I’ll leave the rest of the story for you to discover, but I assure you, Drew and Caroline have quite a journey ahead of them before their happily ever after!

How I relished weaving my characters into history during one of America’s most challenging and fascinating eras. I’ll leave the rest of the story for you to discover, but I assure you, Drew and Caroline have quite a journey ahead of them before their happily ever after!

**One other historical tidbit I found in my research. If you’ve read or seen the movie, Ben Hur, you might find it interesting that it was written by none other than the retired Union General Lew Wallace!!

About the Book

The War brought them together ~ Would it also tear them apart?

The War brought them together ~ Would it also tear them apart?

While en route to aid Confederate soldiers injured in battle near her home, Southerner Caroline Dunbar stumbles across a wounded Union sergeant. Unable to ignore his plea for help, she tends his injuries and hides him away, only to find her attachment to him deepen with each passing day. But when her secret is discovered, Caroline incurs her father’s wrath and, in turn, unlocks a dark secret from the past which she is determined to unravel.

After being forced to flee his place of refuge, Sergeant Andrew Gallagher fears he’s seen the last of Caroline. Resolved not to let that happen, when the war ends, he seeks her out, only to discover she’s been sent away. When word reaches him that President Lincoln has been shot, Drew is assigned the task of tracking down the assassin. A chance encounter with Caroline revives his hopes, until he learns she may be involved in a plot to aid the assassin.

Beyond These War-Torn Lands is available on Amazon

About the Author

Cynthia Roemer is an inspirational, bestselling author with a heart for scattering seeds of hope into the hearts of readers. Raised in the cornfields of rural Illinois, Cynthia enjoys spinning tales set in the backdrop of the mid-1800’s prairie and Civil War era. Her Prairie Sky Series consists of Amazon bestseller, Under This Same Sky, Under Prairie Skies, and Under Moonlit Skies, a 2020 Selah Award winning novel.

Cynthia Roemer is an inspirational, bestselling author with a heart for scattering seeds of hope into the hearts of readers. Raised in the cornfields of rural Illinois, Cynthia enjoys spinning tales set in the backdrop of the mid-1800’s prairie and Civil War era. Her Prairie Sky Series consists of Amazon bestseller, Under This Same Sky, Under Prairie Skies, and Under Moonlit Skies, a 2020 Selah Award winning novel.

Cynthia writes from her family farm in central Illinois where she resides with her husband of almost thirty years. They have two grown sons and a daughter-in-love. When she isn’t writing or researching, Cynthia can be found hiking, biking, gardening, reading, or riding sidesaddle with her husband in the combine or on their motorcycle. She is a member of American Christian Fiction Writers. To learn more about Cynthia and writing journey, sign up for her author newsletter or visit her online at: her website, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, BookBub, or GoodReads.

This giveaway is now closed!

Congrats to Lila, the winner of the signed copy of Beyond These War-Torn Lands!

Giveaway**

Cynthia is giving away one signed print copy of Beyond These War-Torn Lands to one lucky Romancing History reader. To enter, tell us what your favorite period of American history is to read about and why.

**Giveaway ends midnight, August 4th**